December 17, 2022

I spoke at the University of Queensland‘s School of Economics about the factors that contribute to human intelligence. The talk was a broad sweep of my work on intelligence and human evolution, including work in progress. A lot of this work is covered in my forthcoming book, A Theory of Everyone.

Some of the key papers discussed include:

- Schimmelpfennig, R. & Muthukrishna, M. (2023). Cultural Evolutionary Behavioural Science in Public Policy. Behavioural Public Policy. [Publisher] [Download] [Twitter] [LinkedIn]

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A. V., Henrich, J., Curtin, C., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J. & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 678-701. [Download] [Supplementary] [Code] [Summary Post] [Publisher] [Twitter]

- Henrich, J. & Muthukrishna, M. (2021). The Origins and Psychology of Human Cooperation. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 207-40. [Download] [Publisher] [Twitter]

- Muthukrishna, M., Henrich, J. & Slingerland, E. (2021). Psychology as a Historical Science. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 717-49. [Download] [Publisher] [Twitter]

- Muthukrishna, M., Francois, P., Pourahmadi, S., & Henrich, J. (2017). Corrupting Cooperation and How Anti-Corruption Strategies May Backfire. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(0138). [Download] [Summary Post] [Publisher]

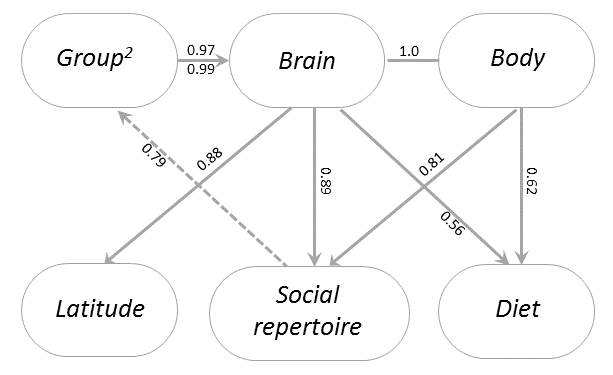

- Muthukrishna, M., Doebeli, M., Chudek, M., & Henrich, J. (2018). The Cultural Brain Hypothesis: How culture drives brain expansion, sociality, and life history. PLOS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006504. [Download] [Supplementary] [Summary Post] [Publisher] [Twitter]

- Muthukrishna, M. & Henrich, J. (2016). Innovation in the Collective Brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1690). [Telegraph] [Scientific American] [Video] [Evonomics] [LSE Business Review] [Summary Post] [Download] [Data] [Publisher]

- Schimmelpfennig, R., Razek, L., Schnell, E., & Muthukrishna, M. (2021). Paradox of Diversity in the Collective Brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. [Download] [Summary Post] [Publisher] [Twitter]

- Uchiyama, R., Spicer, R. & Muthukrishna, M. (2021). Cultural Evolution of Genetic Heritability. [Target article]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1-147. [Download] [Summary Post] [Publisher] [Twitter]